Text by Lindsey Kesel

Images courtesy of the artist

Ai Weiwei has been called a traitor, a hooligan, a lawbreaker, and an agent provocateur. Thanks to his subversive artworks, he lives with a permanent target on his back: In 2009, an assault by plainclothes police officers in Chengdu, China, sent him to the hospital with a cerebral hemorrhage; in 2011, Chinese authorities detained and imprisoned Ai for political dissidence, under the guise of tax evasion; in 2018, his Beijing studio was demolished without warning—the second art space of his to be razed. But for all the perils he has endured, Ai refuses to be silenced.

Ai’s multifarious body of work boldly defies agents of tyranny and transgression, including his motherland of China, branding him an antihero for the oppressed. His statements on the absurdity of what is—tackling heavy issues such as censorship, state surveillance, and human rights violations—are fueled by hope for what could be.

“I’m an eternal optimist,” he says in Ai Weiwei: Never Sorry, the 2016 documentary about his life. “I think optimism is whether you are still exhilarated by life … whether you are curious, whether you still believe there is possibility.”

Disruption of the status quo is Ai’s birthright. His father, Ai Qing, was a famous poet, imprisoned and exiled to Western China shortly after his son’s birth in 1957 for his rightist views criticizing the Communist regime. Growing up in a labor camp, Ai’s front-row seat to displacement and suffering was the catalyst for his eventual life of activism.

If you know who you are, you’re not a real artist,

Ai Weiwei

A rare breed of artistic shapeshifter, Ai toggles among wildly diverse mediums dictated by the demands of his subject matter—everything from sculpture, architecture, and performance art to blogging, filmmaking, and heavy metal music. During a virtual appearance at the Hawai‘i Contemporary Art Summit in February 2021, Ai spoke about the need for perpetual introspection and fresh challenges in making art.

“If you know who you are, you’re not a real artist,” he said. “You have to put yourself in danger … constantly in doubt about your fixed ideas.”

Some of Ai’s most impactful works are those inspired by his experiences with imprisonment, invasion of privacy, and other forms of control.

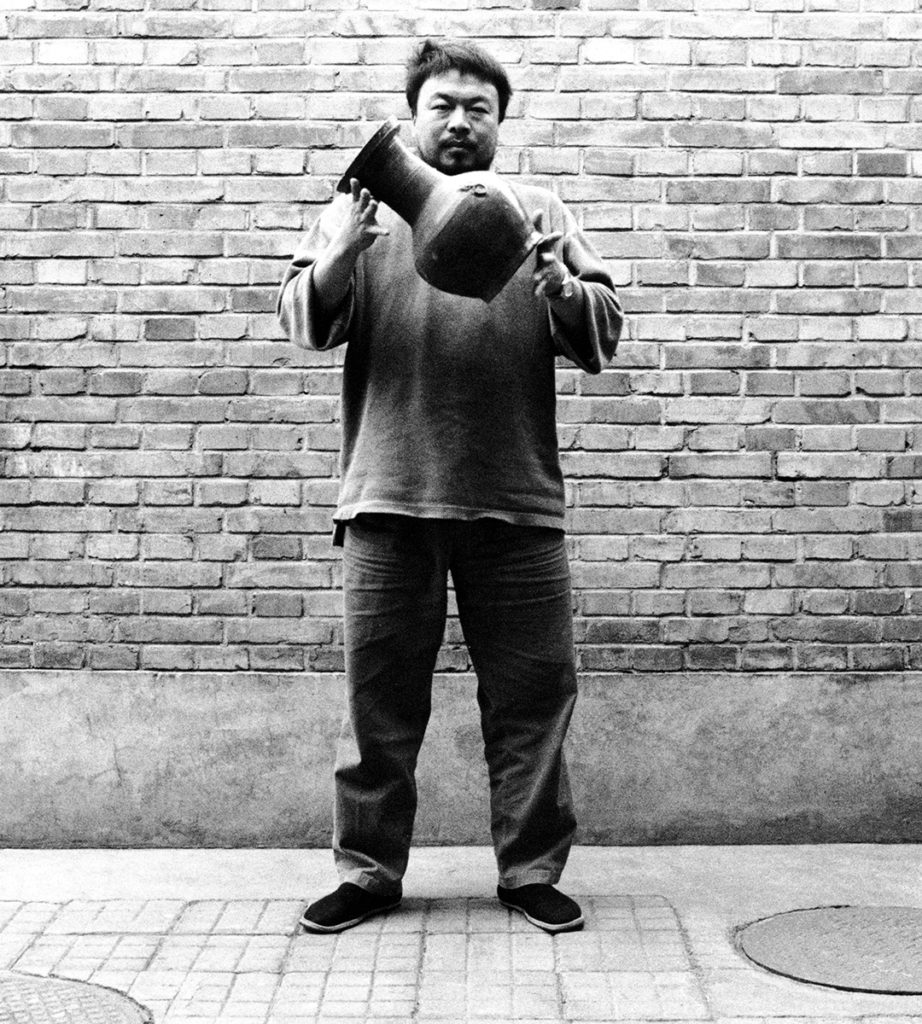

One of Ai’s first big shockwave pieces is “Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn” (1995), where he immortalized himself destroying a 2,000-year-old ceremonial artifact in photographs—a commentary on China’s clash of tradition versus modernization. Probably his most controversial work is the Study of Perspective (1995–2017), a series of photos featuring Ai’s middle finger aimed at what he deems harbingers of censorship and suppression around the globe: the Eiffel Tower in Paris, the White House in Washington, D.C., and Tiananmen Square Gate in Beijing. His Tiananmen Square image, a blatant reference to the 1989 massacre of peaceful student protesters, was a major focus of the interrogation that led to Ai’s 81-day incarceration in 2011.

“I’ve been under restriction for a long time,” he says during the Hawai‘i Contemporary Art Summit talk. “And those obstacles only stimulate me or encourage me to respond, to act.”

A year after his arrest, Ai put himself under surveillance and invited the public to view a live feed of four webcams in his Beijing home for a cheeky piece titled “Weiwei Cam.” In the sculpture “Surveillance Camera” (2010), a likeness of a CCTV camera carved in marble—sourced from the same quarry as Chairman Mao’s mausoleum—taunts Chinese authorities who had him under 24-hour surveillance at the time.

I’ve been under restriction for a long time. And those obstacles only stimulate me or encourage me to respond, to act.

Ai Weiwei

Confined to China after his incarceration, in 2014 Ai coordinated more than 100 collaborators to execute the seven-part exhibition @Large: Ai Weiwei on Alcatraz from his Beijing studio. In one section of the former federal penitentiary, “Trace” featured portraits of 176 international prisoners of conscience, including Nelson Mandela and Edward Snowden, created entirely from Legos. During the seven-month show, guests were invited to write postcards carrying messages of hope and support to the prisoners.

Ai is often moved to include gestures of camaraderie for victims of political corruption and negligence. After an 8.0 earthquake hit China’s Sichuan province on May 12, 2008, he orchestrated “Straight” to spotlight government malfeasance in the form of shoddy school construction. The 90-ton floor sculpture involved reclaiming 150 bars of mangled steel rebar from schools that crumbled in the disaster, and straightening them by hand. To honor the students who lost their lives that day, Ai led a volunteer effort to collect over 5,000 of their names and birthdays and posted the list to his blog on the earthquake’s one-year anniversary.

More recently, Ai has been busy making films that convey the gritty, intimate details of injustice, from the global refugee crisis to police brutality. For the 2020 film Coronation, he directed a covert camera crew in Wuhan, China, during the military-style coronavirus lockdown of more than 10 million people. Whatever Ai Weiwei manifests next, it will be equal parts unexpected and meaningful, with a dash of goodwill. In 2017, Ai rekindled the spark of his Study of Perspective series by casting rhodium-plated models of his illustrious hand, middle finger pointed high. Auctioned off to raise money for New York City’s Public Art Fund, the run of 1,000 mini sculptures sold out in a few hours.