Text and images by Roger Bong

Step into a record shop or antique store and you’ll encounter an artform now 80 years old: the album cover. To spend an hour at Hungry Ear Records or Idea’s Music and Books in Kaka‘ako is to dive into a rich landscape of visual stimuli designed for decades to pique your interest and, ultimately, convince you to buy the music behind the artwork.

Album cover design began with a desire to increase sales. In 1939, Columbia Records’ art director Alex Steinweiss convinced the vice president of sales to let him personally design covers to accompany records. Soon, records with covers sold ninefold better than those without. The industry was changed forever.

Hawai‘i-based record companies began popping up after the Second World War in tandem with increased tourism to the islands. These new local labels, including Hula Records, Waikiki Records, and 49th State Records, competed with the national labels that had been recording Hawaiian music since the early 20th century, like Columbia and Victor. At first, they pressed music to fragile 10-inch shellac discs that held one song per side. Then, in the 1950s, the introduction of the 12-inch vinyl LP attracted a greater record-buying audience, providing the convenience and affordability of unbreakable discs that held 20 minutes of music per side. Local labels welcomed this era by transforming music they had already recorded into countless albums and then putting on the covers romantic phrases and idyllic images of Hawai‘i. The label 49th State compiled a series of albums titled “Authentic Hawaiian Melodies Recorded In Hawai‘i” and used stock photos like hula dancers entertaining malihini or a lone surfer at Hana Bay for artwork. Album titles like Enchanting Hawaiian Holiday unabashedly marketed to visitors.

This generic formula subsided in the 1960s when artists like Gabby Pahinui and Sonny Chillingworth released albums with down-to-earth images of themselves on the covers. Chillingworth’s first album, Waimea Cowboy, shows the guitarist standing in a forest with the words “Hawaiian Slack-Key.” His 1967 eponymous album used a photo from the same shoot and omitted any text about Hawai‘i. Was it from Hawai‘i? It didn’t matter, at least for the album cover. Finally, musicians and art directors had the creative freedom to design covers rather than adhering to the often restrictive, well-worn marketing approach of attracting listeners by depicting Hawai‘i as an idyllic place of surf, sand, and enchanting sound.

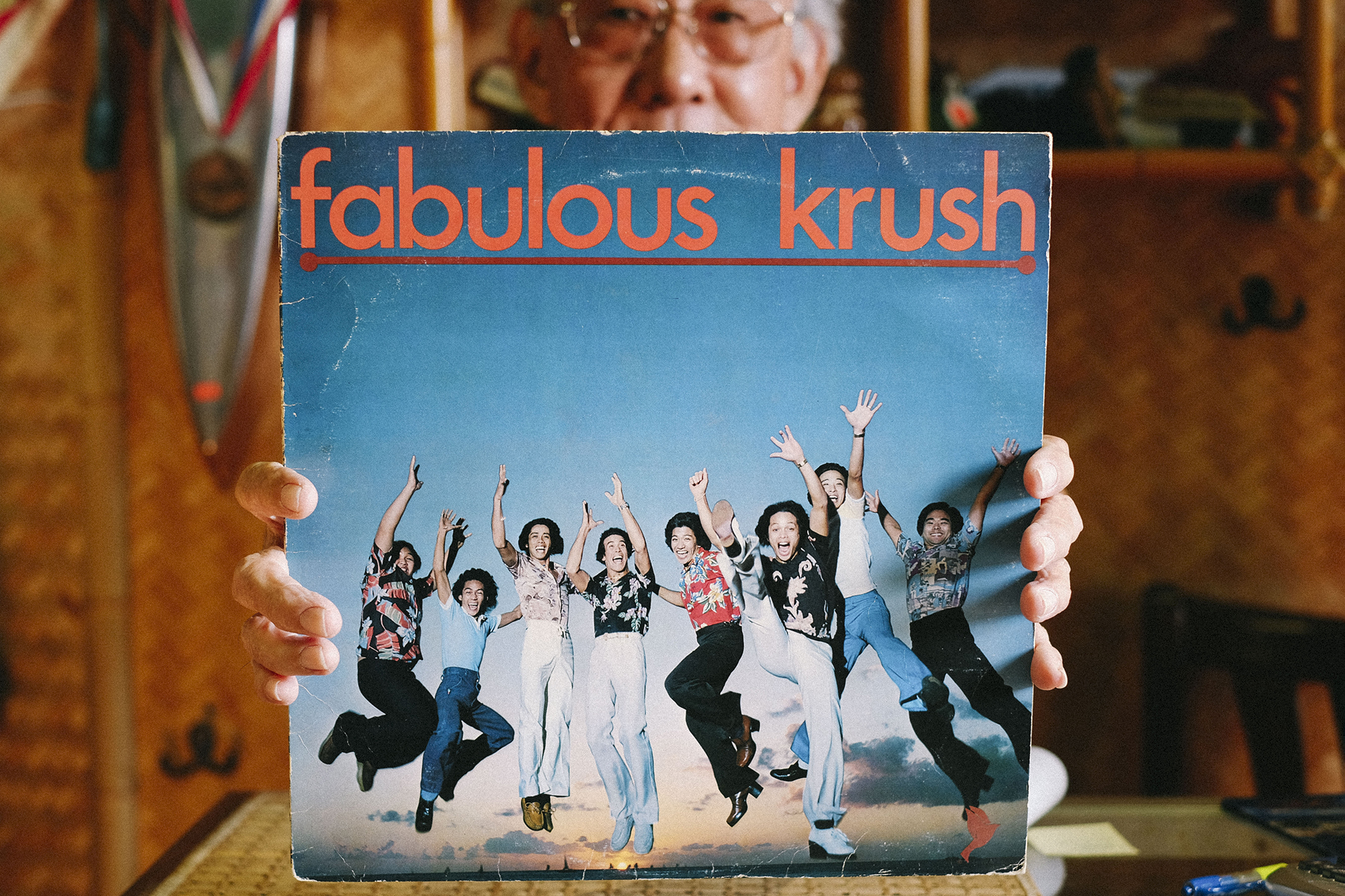

The 1970s saw contemporary groups adopt custom-branded insignia and reinvent Hawai‘i’s marketing appeal. The most recognizable logo of the era is that of Kalapana, which features an all-lowercase, rolling typeface reminiscent of the ocean. The band has used it almost exclusively from its 1975 debut to its most recent 2018 Best Of collection. Fabulous Krush’s self-titled album featured aloha-shirted band members jumping above the horizon at sunset. Others wanted not to market Hawai‘i but rather to pay tribute to Hawaiian cultural values or heritage. ‘Āina chose an illustration of a Hawaiian man existing in harmony with the land and sky. Momi, a Native Hawaiian harpist and singer, posed in a stunning portrait wearing a haku lei.

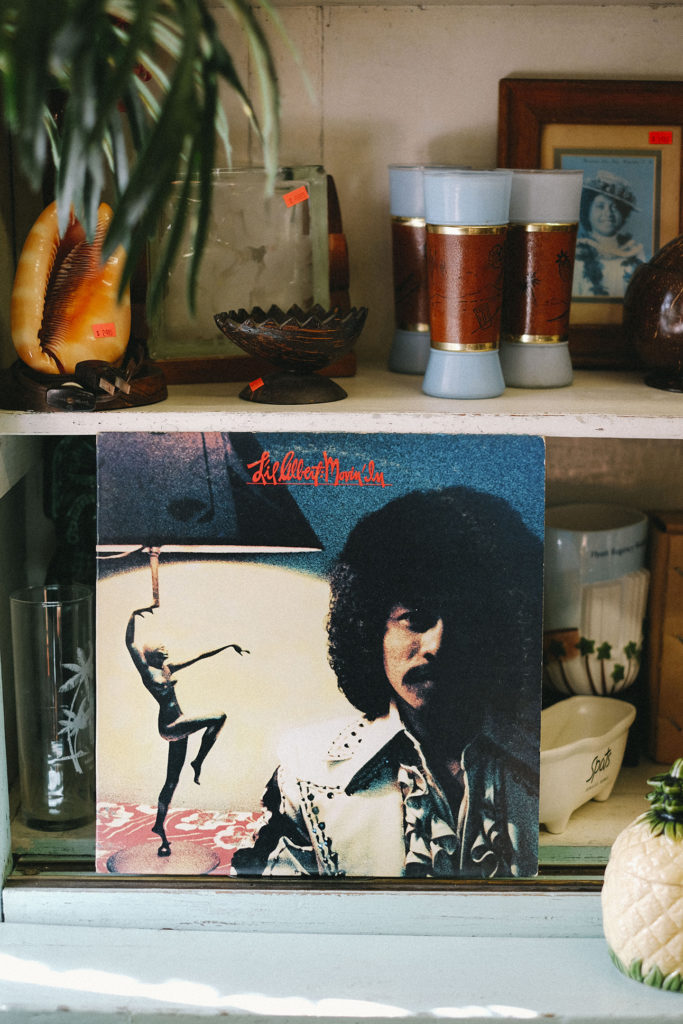

Many local artists during the 1970s and 1980s made original music not to satisfy Hawai‘i’s visitor economy but to participate in the global music scene where R&B, rock, jazz, disco, and soul music topped charts. The album covers often reflected this, void of any visual cues indicating the music was “Hawaiian.” Kalapana’s lead singer, Mackey Feary, debuted his solo album with a photograph of Honolulu’s city lights. You couldn’t guess the city unless you knew the view. Jazz-fusion group Music Magic went wild with a psychedelic illustration of the members (or their spirit animals) jamming in a futuristic landscape. Lil Albert appeared in a soulful, subdued portrait in which the only hint of Hawai‘i was a floral-pattern tablecloth. Loyal Garner’s 1981 self-titled release avoided any island reference, opting to glamourize the singer’s likeness in a simple monochromatic illustration.

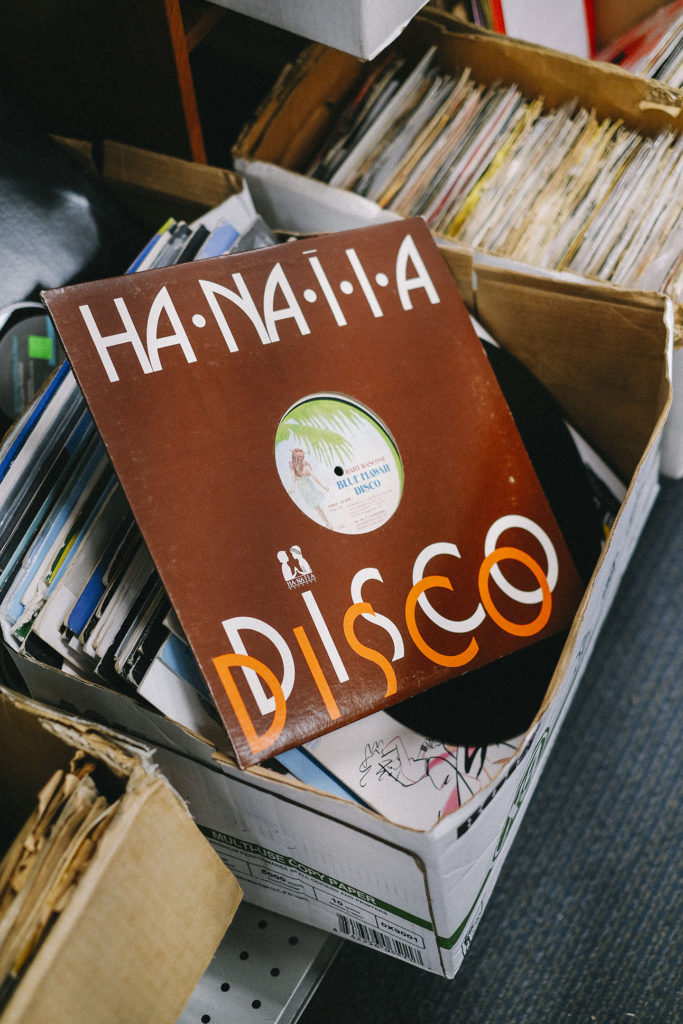

Even for album covers that did show off some island flair, global music culture remained a strong influence on local album design. Al Nobriga’s They’re Playing My Music placed the singer-songwriter in a decidedly disco setting on Kalakaua Avenue wearing flared pants next to an attractive, rollerskating woman. Bart Bascone’s 1979 Blue Hawaii Disco followed the genre’s format of placing big, bold letters on the jacket (“HA•NA•Ī•I•A DISCO”) to tell customers it was a dance record. Mackey Feary and Nohelani Cypriano released a bold-texted dance single, too: Let’s Do It!

Album covers act as windows into the souls of artists and their music. As the founder of Hawai‘i record label Aloha Got Soul, I also attempt to create covers that best represent the music. In doing so, I ask the same questions other designers have asked since the album cover’s inception: What does the record sound like? What kind of person is the artist? How can the artwork attract the most listeners?

For Nick Kurosawa, a soul singer on the Aloha Got Soul label, his childhood played an important part in his musical upbringing. For the cover of his self-named album released in 2018, I photographed him at his family home in Mānoa Valley. Reggae producer Ryan “Jah Gumby” Murakami, who prefers to keep a low profile, makes music as rich and deep as his record collection. To represent the organic, multi-layered music of his release Humility: The Vibes of Jah G, I made a complex collage of hundreds of photographs of his home studio that showcased not only his instruments and recording gear but also his prized collection of more than 10,000 LPs.

Each album cover tells a story beyond the music—the dreams of the musicians, the skill of the designer, and the hopes of the album’s producer. It is meant to best represent the soul of the sound a person will hear, even if the listener has yet to place the needle on the record or press play on a phone.

Roger Bong is the founder of Aloha Got Soul, a music label inspired by record-digging culture with a focus on Hawai‘i’s music from the 1970s and ’80s.