Text by Christine Hitt

Images courtesy of Allison Leialoha Milham

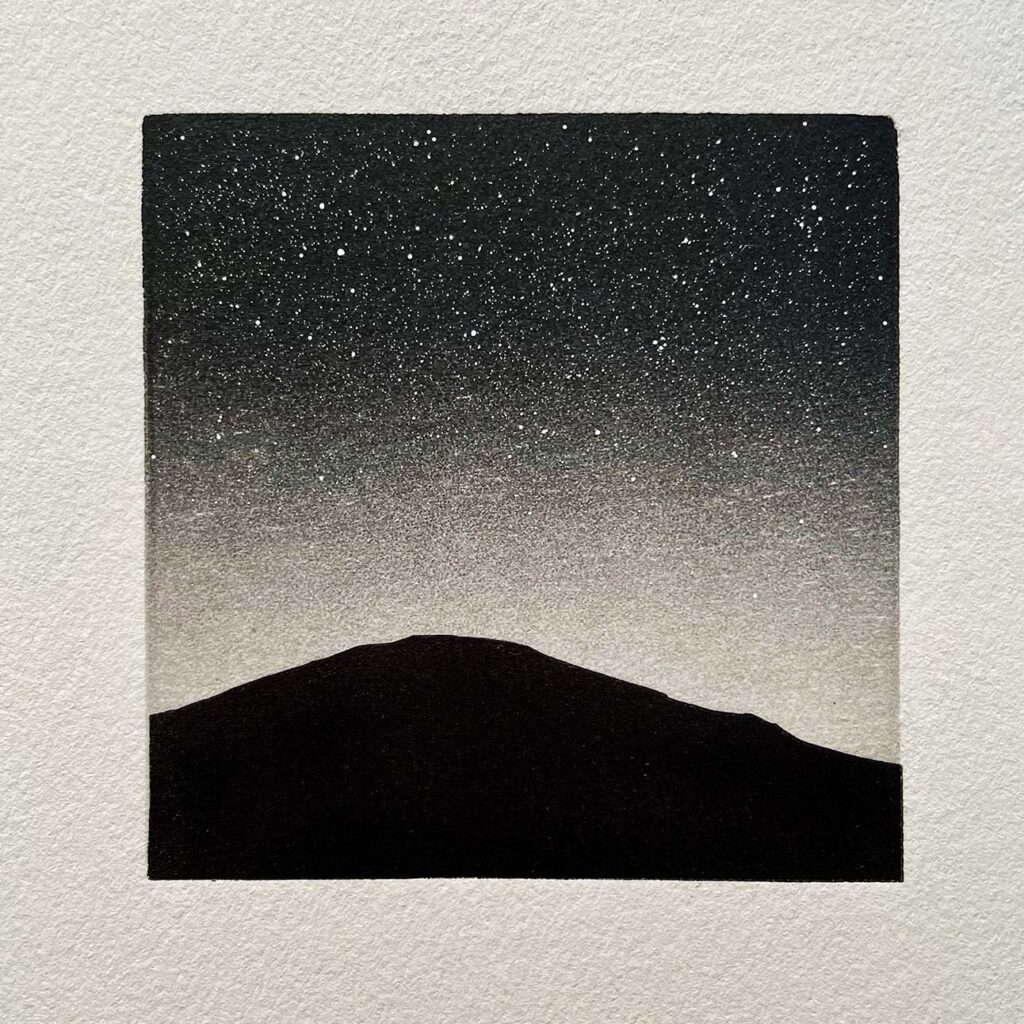

On opening a square black box adorned with an image of a dark mountain and sky full of stars, a melody begins to play. A woman’s singing voice rises from a sound piece hidden within, its soulful lyrics speaking of “he pilina wehena ‘ole,” or an unbreakable bond.

The song was composed by artist Allison Leialoha Milham during a month-long residency at Hawai‘i Volcanoes National Park in 2018. Mourning the loss of her mother, Native Hawaiian journalist and activist Mary Alice Ka‘iulani Milham, the artist found solace amid the volcanic landscape of the island of Hawai‘i. “She was a huge part of my life,” Milham says. “The music speaks to my early experience of grieving, and this sense of knowing our relationship is ongoing.”

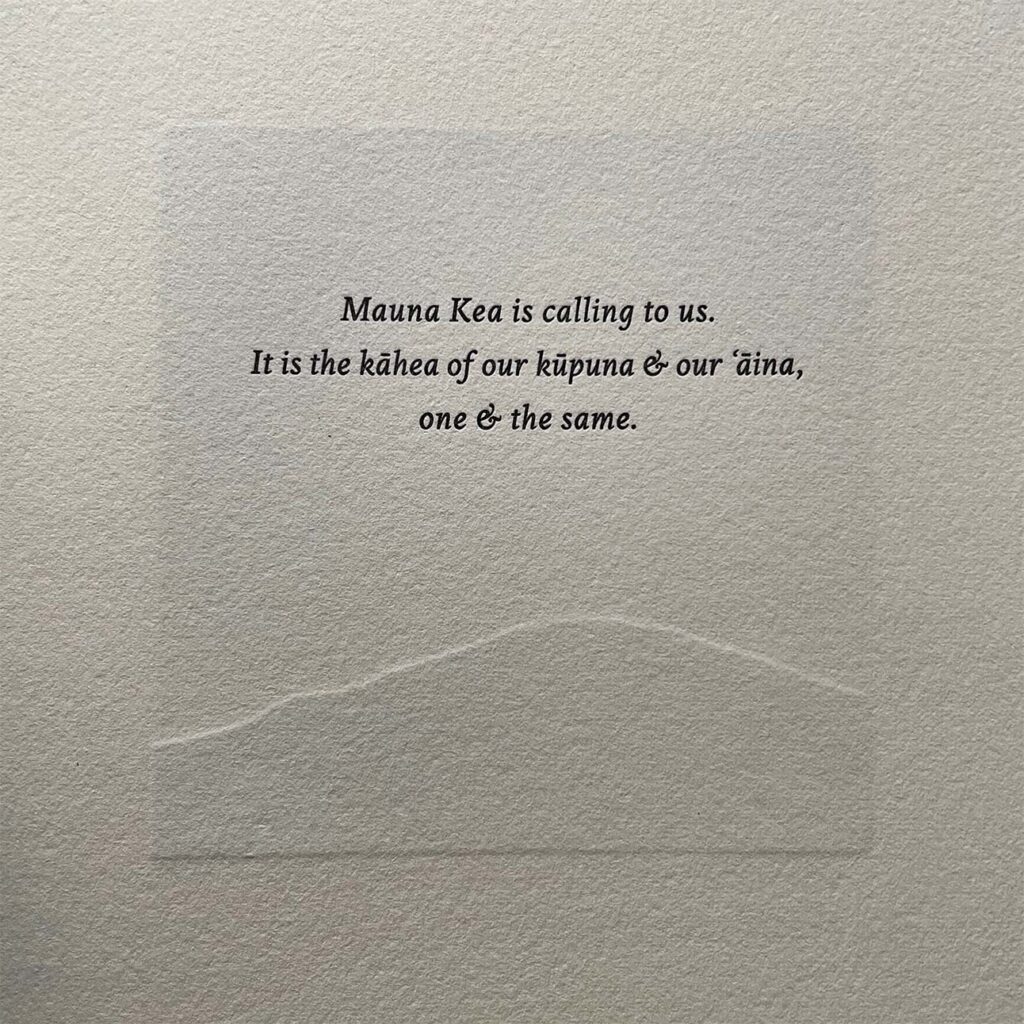

Born and raised in California and now residing in Oregon, Milham maintained a connection to Hawai‘i largely through her mother, who was a vocal advocate for Hawaiian sovereignty and the fight to protect Mauna Kea. With her passing, Milham desired to forge her own unique connection, or pilina, with the land that bonds her not only to her mother but also to a long line of Hawaiian ancestors who provide inspiration.

Out of this reflective healing sprung Pilina Everlasting, the enigmatic black box with its serene illustration of Mauna Kea on the cover. Completed in 2022, the work has been collected by more than 50 institutions, including the University of California, Berkeley, Bainbridge Island Museum of Art in Washington, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Combining graphic design, printmaking, bookbinding, and music composition, the project is a cache of treasures: letterpress prints of text and images on handmade paper, a booklet featuring “Mauna Kea Calling,” an essay by Milham’s mother, a book of images representing the Hawaiian goddesses Pele and Hi‘iaka, and a 7-inch vinyl record of the song Milham wrote during her cathartic residency on Hawai‘i Island. “The end of the song has part of the oli (chant) Nā ‘Aumākua, which was my mom’s favorite oli, and one she started teaching me,” she says.

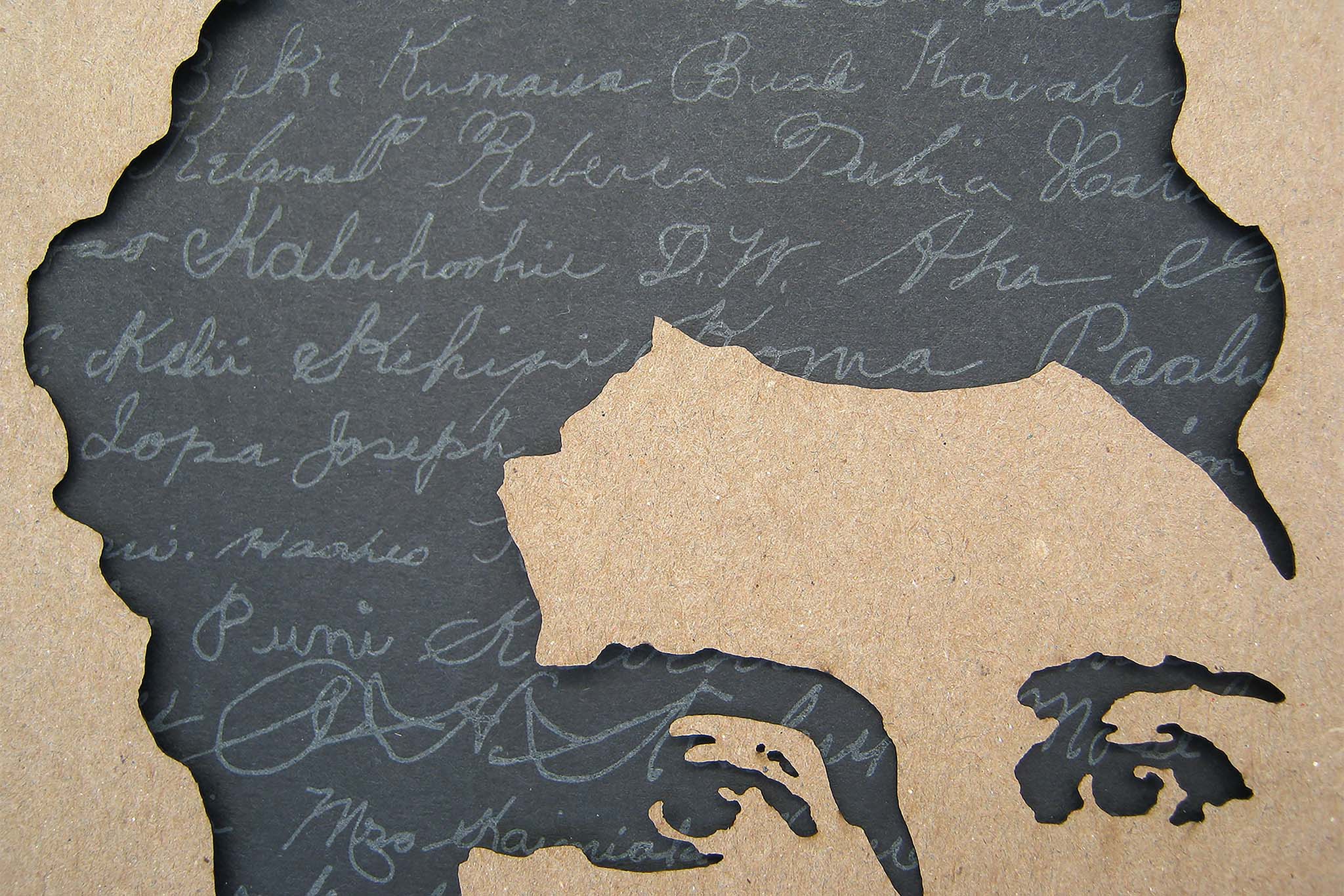

Music plays a key role in much of Milham’s life and work. After graduating from the University of Alabama with a master’s in fine arts in 2012, the singer, songwriter, and musician taught book arts across the country while recording music and creating visual art. That same year, she released Uluhaimalama: Legacies of Lili‘uokalani, a multimedia box set exploring Hawaiian history through Queen Lili‘uokalani’s music and legacy. Like Pilina Everlasting, the work is a trove of poignant objects and ephemera: postcards, a booklet, a stencil of the Queen, and a record of Milham performing Lili‘uokalani’s songs.

All of the items in the box set speak to the Queen’s graceful leadership and resistance to U.S. domination, a legacy that continues to inspire activism in Milham and other Hawaiians today. “There are things that a lot of people who go to Hawai‘i for vacation, or even those who live there as settlers, still don’t have a handle on—the fact that there was never a treaty of annexation, that Hawaiians never relinquished their sovereignty, and all of the impacts of U.S. colonialism and militarism in Hawai‘i,” she says.

Future projects include illustrating a book for a poet and author, and illustration and design work in collaboration with musicians remaking old Hawaiian string band songs. Milham is especially excited about a potential large-scale project centered around the history of print in Hawai‘i. “I learned early on in my education and in letter press printing and book arts that Hawai‘i had printing presses before the West Coast of the continent, and crazy-high literacy rates,” she says. “I’m really interested in diving more into that.”

Devoted to championing Hawaiian independence and Indigenous rights in her work, Milham is continually inspired by the fierce Native Hawaiian advocates who came before her. Her grandmother, the late Dallas Keali‘iho‘oneaina Mossman Vogeler, was a theater director and activist who directed a five-day, real-time reenactment of the Overthrow of the Hawaiian monarchy as part of the Onipa‘a Centennial Observance at ‘Iolani Palace in 1993. “She—and my mom, too, being a writer—both modeled how to use your art and your passion to help support what you believe in,” Milham says. “I’ve tried to figure out how to use my gifts and skills as an artist to support these things that I care deeply about from afar.”