Text by Anna Harmon

Images by IJfke Ridgley

Northern New Mexico was dry as a bone in early July. The hiking paths at Ghost Ranch were closed in case the juniper, cedar, cholla, piñon pine, and sagebrush that swelled and scattered across the landscape were to catch fire. Families there for a retreat buzzed around the campus’s main building as I looked for signs of Georgia O’Keeffe. Where had she walked? What had she painted? Just to the left, a guide pointed out, was the tiny house where O’Keeffe first stayed at the ranch in 1936 after traveling to Taos for several summers.

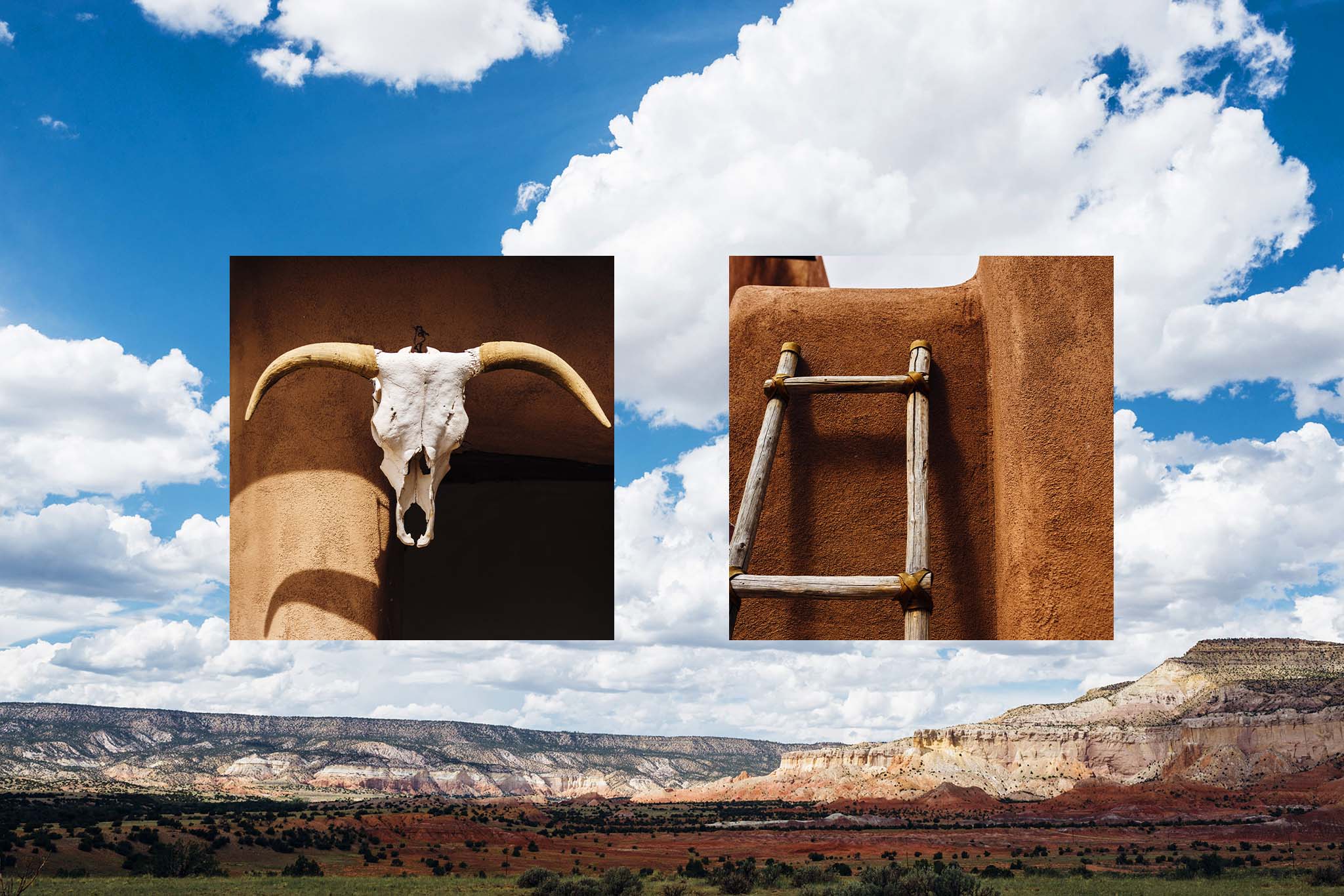

Now you could pay a surprisingly affordable amount to sleep there. Nearby, a bleached cow skull hung on an adobe wall. In the distance was a mountain with a sheared top that I later learned was Cerro Pedernal, a consistent muse of O’Keeffe’s. After she died at the age of 98, her ashes were spread atop it on a windy day.

Soon I boarded a small bus to see spots around the ranch that O’Keeffe had immortalized in oil on canvas. With multicolored mesas surrounding us and junipers twisting up from the earth in all directions, it was hard to narrow down what qualified for painting. O’Keeffe’s choices were even more difficult to predict.

While other Western artists who came to New Mexico before the 1930s, and those who came well after, often tried to capture the entirety of the overwhelming vistas, O’Keeffe instead relished the details. She enlarged small mesas, centered the crevasses and mounds and skylines that gave rise to shapes in her mind.

She did not paint cowboys or young Native women or reverent worshippers in packed Catholic churches, as some of her contemporaries did. Nor did she make portraits of fellow independent white women who were heading southwest. Instead, she looked to the skeletons of the earth.

O’Keeffe spent her childhood in Wisconsin and Virginia and then studied art in Chicago and New York. After brief stints teaching and painting in Virginia, South Carolina, and Texas—where she soaked up the open sky and moods of the plains—she moved to New York in 1918. Beforehand she took a trip to Colorado with her sister, during which she first fell for Santa Fe. Then, in 1929, wealthy art patron Mabel Dodge Luhan invited the increasingly renowned modernist artist to her property in Taos.

Just as the Southwest had been painted as new territory to be claimed—willfully erasing or exoticizing the Native peoples and Mexicans thriving there—the region held a similar new-world promise for Western artists: The sky unrolled in New Mexico; the earth proffered fresh colors. It seemed raw and dangerous and overwhelming and quiet and pure.

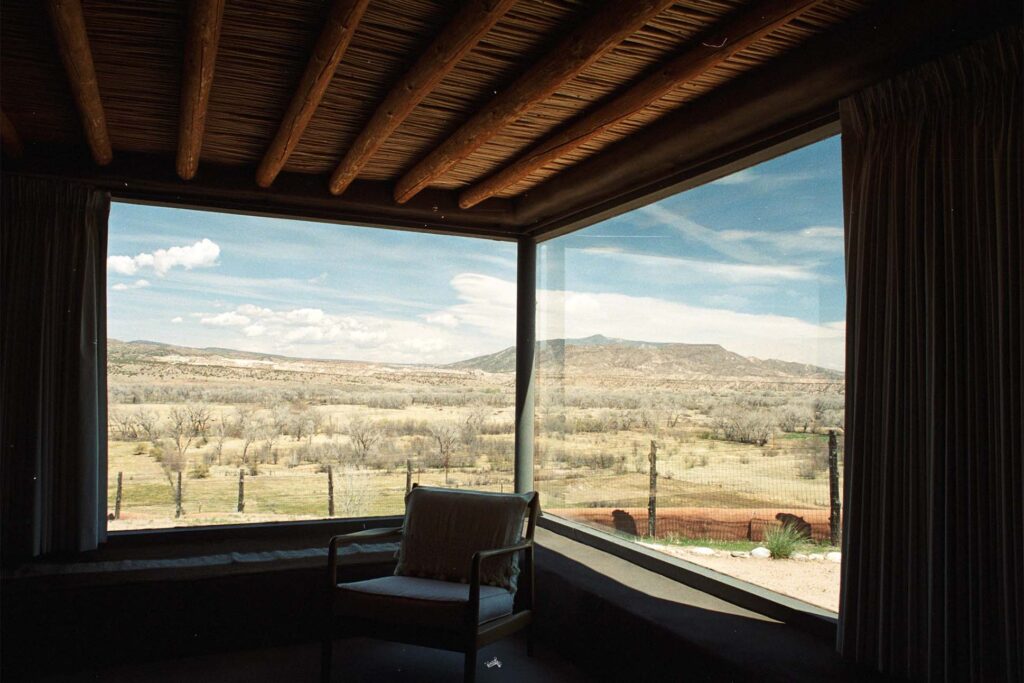

Already averse to the rich green and wetness back east, O’Keeffe increasingly favored this setting. She turned a Model A Ford into a traveling studio and bought a house in a more remote area of Ghost Ranch. She spent decades of summers there. Looking at her paintings alongside the landmarks, I got the sense that she was both exposing their bones and giving the land fluidity. She infused crumbly grey hills with deep reds and lavenders that she observed in different moments of the day.

“I wish you could see what I see out the window,” she wrote to friend and fellow painter Arthur Dove in September 1942, “the earth pink and yellow cliffs to the north—the full pale moon about to go down in the early morning lavender sky behind a very long beautiful tree covered mesa to the west—pink and purple hills in front and the scrubby fine dull green cedars—and a feeling of much space. It is a very beautiful world.”

In 1945, she purchased a second property in the nearby town of Abiquiú at which to winter. The day after my tour of Ghost Ranch, which is now owned and operated by the Presbyterian Church, I headed to this house. In 1949, it became her permanent residence when she was not summering at Ghost Ranch, travelling the globe, or setting out with friends like nature photographers Ansel Adams and Eliot Porter.

Getting to the home required another ride in a small shuttle, as the village of Abiquiú was protected by a historic land grant and therefore not open to an increasing rush of visitors. Now managed by the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum in Santa Fe, this house was largely how the artist left it before she died in 1986.

Dozens of rocks she had collected rested on a boulder outside the expansive windows of her workspace and bedroom. A makeshift ladder to the rooftop leaned against the adobe wall, just as a ladder was still propped up at her house on Ghost Ranch. Even the clothes she made for herself hung in the closet.

For a moment, on the tour, you could pretend you were the rare guest taking a quiet moment to soak up her essence.

In 1965, when O’Keeffe was nearly 80 years old, she painted a mural-size cloudscape in her garage at Ghost Ranch. Seven years earlier, she had made her last known painting of Cerro Pedernal, a sacred place to several indigenous peoples. In it, the mountain is a tiny speck among a dark range along the bottom of the canvas. Between this and a half moon, a yellow ladder floats in the open blue.

O’Keeffe became a common sight around Ghost Ranch and Abiquiú, where she took long walks, according to the tour guide.

Now anyone can watch a livestream of her garden at the Abiquiú house. On Mondays, during the growing season, it gets its weekly allotment of water from the acequia system. The trenches flood and then the water subsides.

It’s as if nothing has changed, except O’Keeffe is both not there, and she is everywhere.