Text by Rae Sojot

Images by John Hook and John Bilderback

In Spring 2023, the Polynesian Voyaging Society will launch one of its most extensive campaigns yet: a 41,000-mile, 42-month circumnavigation of the Pacific. Coined the Moananuiākea Voyage, sister canoes Hōkūleʻa and Hikianalia will sail the ancient sea roads, visiting 46 countries and archipelagoes, 100 Indigenous territories, and 345 ports along the way. The four-year journey is a monumental undertaking, but a crucial one—an effort to reconnect with other Indigenous communities and build relationships with those not yet visited.

Here, three PVS members share personal voyaging stories from aboard Hōkūleʻa, reflecting on the lessons learned and the relationships forged along the way.

The Young Navigator

For 24-year-old Kai Hoshijo, teamwork really does make the dream work. In 2021, she and four other young crew members from PVS were selected to sail Hōkūleʻa to Nihoa, an island in the uninhabited Northwestern Hawaiian Islands. The journey—a relatively smooth two-day stretch across 280 miles—was known for one key navigational challenge. “The difficulty,” Hoshijo says, “is that Nihoa is so small.”

The opportunity to test their burgeoning voyaging skills without the use of modern navigational tools was both thrilling and nerve-racking, Hoshijo admits. Although the journey would include senior society members, the young crew members represented the organization’s next vanguard of navigators, and so the pressure was on.

They spent hours poring over maps to create a sail plan, followed by hours of fine-tuning it. Once at sea, they rotated stations—from maintaining the steering blade and keeping the mark from the back corner, to scanning for cues from sea and sky. Sailing into the night, the young crew fell into a natural, easy rhythm. Lacking watches, they measured time by the stars. “We kept switching off every 15 minutes or so,” Hoshijo says. “We just got into a flow.”

Hoshijo and the others had pinned their hopes on the sunrise. Because Nihoa, measuring less than 1 square kilometer, is situated northwest of Hawai‘i, timing was critical. “The sun will rise in the east and then shine on the island,” Hoshijo explains, noting that the window, however, is small. “If you don’t have that, you might just sail past it and then you’re lost.”

But as night slowly crested into dawn, only a vast ocean surrounded them. Doubt crept in. Do we keep our line? Do we switch our line? None of them had ever spotted an island on their own before. “It was like, ‘What are we looking for?’” Hoshijo says.

Two more hours had passed when suddenly crewmate Nālamakū Ahsing spotted an irregular blur fixed on the horizon. Some 35 miles away, a small triangle had appeared. “Like a cloud that didn’t move,” Hoshijo remembers. It was Nihoa. A torrent of emotion washed over Hoshijo, first relief then sheer elation at what they had accomplished. On deck, the crew exploded into joyous celebration. “It was very powerful for us to have our teachers there to see how we came together and supported each other through the process,” Hoshijo says. “I think it was powerful for them too.”

That moment left an indelible impression on Hoshijo and crystallized for her the myriad lessons Hokūlēʻa offers: the importance of generational knowledge, the power of commitment and hard work, the ability to trust oneself and others. “To have five young people laulima (work together) to make something happen,” she says, “it’s more than just sailing. It’s values.”

The Good Doctor

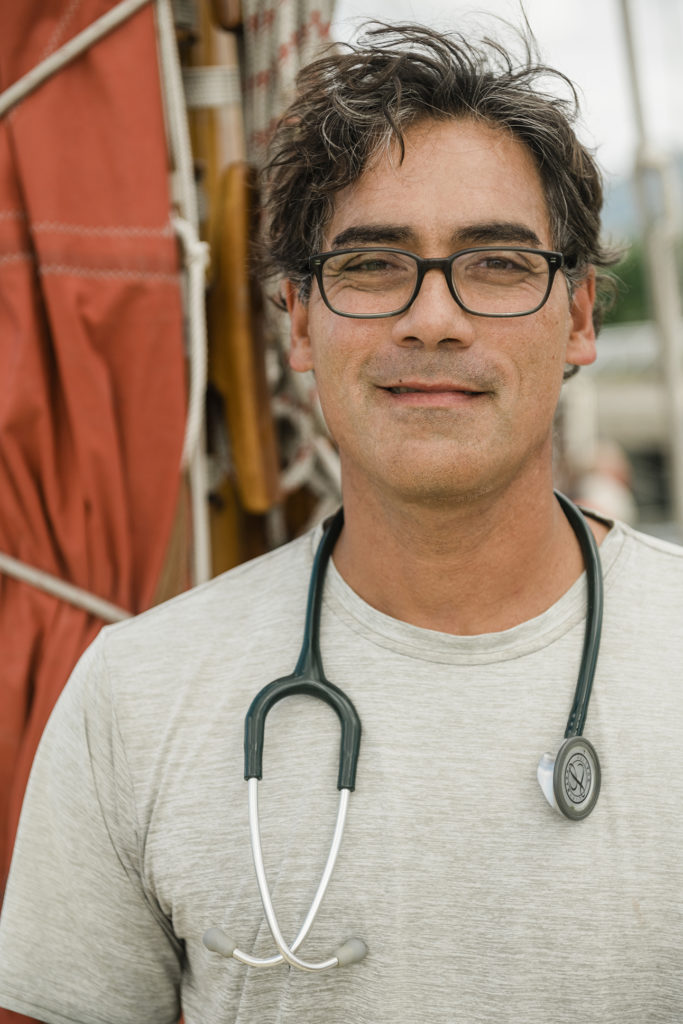

Kelly Tam Sing remembers the palpable excitement surrounding Hōkūleʻa’s maiden voyage from Hawaiʻi to Tahiti. It was 1976, and Tam Sing was five years old. “Everybody was talking about Hōkūleʻa,” he recalls. “It was a huge deal.” For the young Tam Sing, who loved the ocean, Hōkūleʻa represented the stuff of dreams and adventure at sea.

Nearly five decades later, Tam Sing now lives out a small slice of that childhood dream as one of Polynesian Voyaging Society’s volunteer medical officers. Tasked with handling any medical concerns that arise while voyaging, Tam Sing notes that his background and skill as an emergency medicine doctor comes in handy, saying, “You have to be able to take care of anything that comes along.”

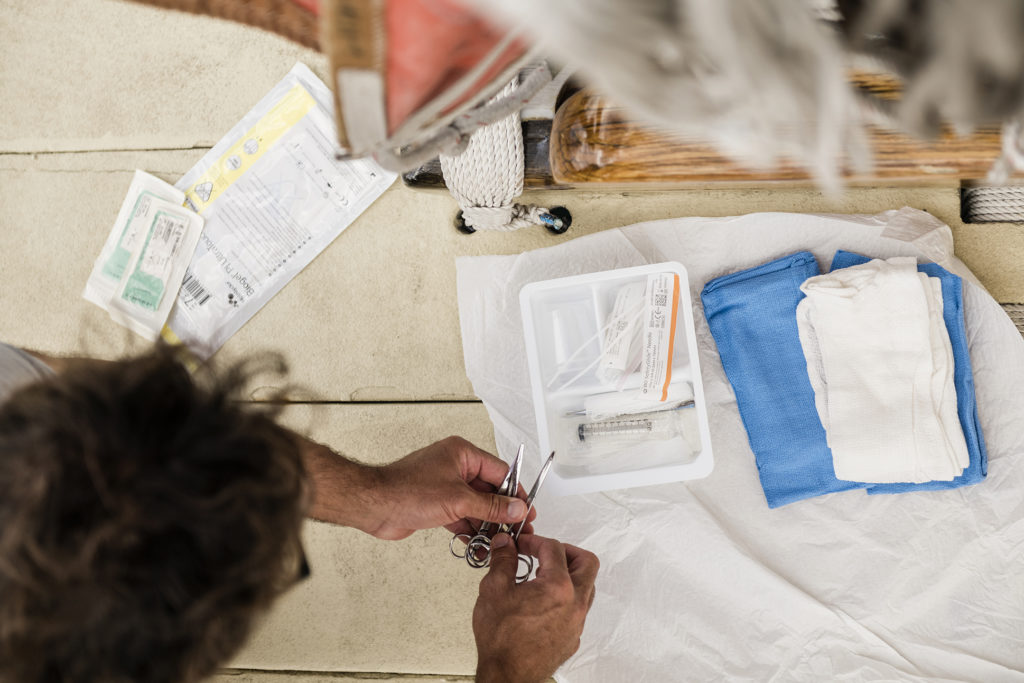

At sea, triage, treatment, and recovery all happen on deck without the accouterments of a fully staffed and supplied ER center. The ability to think on one’s feet and do more with less is key. “You make do with what you have,” Tam Sing says, referencing the three cooler chests lashed to the deck. Inside, medical supplies are packed tight: gear for suturing wounds and abscesses, IVs for fluid resuscitation, chemical ice packs, and specialized medicine for pain and sedation.

The most common ailments include seasickness, sunburn, and constipation. “Constipation is an issue because there is no privacy on the canoe,” Tam Sing explains. “Everyone gets shy.” Thankfully, Tam Sing adds, the more experienced the voyagers, the fewer hang-ups along the way.

Although practicing expedition medicine fulfills Tam Sing’s love for travel and adventure, his work with PVS strikes a deeper, more personal chord. Prior to joining the organization in 2007, Tam Sing, who is of Hawaiian descent, felt detached from his Native identity. PVS gave him a bridge and a meaningful way to contribute to his community.

“I feel more connected to my culture because I am more connected to my community,” Tam Sing says. “I can give my services as a way to honor my ancestors.”

As preparations for the Moananuiākea Voyage get underway, Tam Sing’s perennial focus is the health and safety of the crew. “I’m always looking to preempt and prevent any kind of medical disaster,” he says. He humbly waves off any potential hero status that accompanies his role. Instead, Tam Sing notes this positive paradox: a successful journey is one where his expertise is never needed.

The Master Student

Nainoa Thompson, exemplary Native Hawaiian navigator and PVS president, has always been drawn to the water. As a child the ocean was his refuge; as a man it has become the fulcrum of his life’s work with Hōkūleʻa. But, when asked if he considers himself a “master navigator,” he is quick to disclaim the title. “Oh, I never say that,” he says, with visible embarrassment. “I’m a student, but thank you.” His words are sincere.

Growing up, Thompson struggled in school. His saving grace was an instinctual impulse to search for a teacher. “For me, it’s always been that if you need to learn something,” he says, “go find the person who knows.” During Hōkūleʻa’s nascent years in the ’70s, this approach would be the linchpin in first recovering and then relearning ancient voyaging traditions. “We were trying to do stuff that no one was doing anymore, but we had no manual or blueprint to follow,” he recalls. So he did what he’d always done before: He sought out teachers.

Today, Thompson credits his own navigational success to a storied list of individuals who helped to revitalize the art of traditional wayfinding: PVS founder Herb Kane; big-wave surfer Eddie Aikau; his father, Myron “Pinky” Thompson; and Micronesian master navigator Mau Piailug. “The Hōkūleʻa began as a kind of cultural renaissance recovering traditions,” Thompson explains. “Today it’s evolved into protecting what we learn and honoring our teachers.” That list of teachers continues to grow.

Now in his late sixties, Thompson shares that he sometimes contemplates a solo voyage from Tahiti to Hawaiʻi, a feat that his close circle considers a crazy endeavor. The voyage is challenging enough for a full crew, but to sail Kealaikahiki, the ancient sea road to Tahiti, on one’s own? Thompson, a private man, offers a simple response: He wouldn’t be alone. “My crew would be my father,” he answers, “it would be Mau and Eddie too … We carry our teachers with us.”