Text by Noelani Arista

Images by Joey Trisolini and courtesy of Paul Pfeiffer

The cool interior of a large room doubling as an exhibition space at McCoy Pavilion offered welcome respite from the sun-soaked concrete pathways of Ala Moana Beach Park. My two sons and I took a seat in the womb-like space, ensorcelled by two large video screens positioned side by side but aimed off-kilter toward one another, both projecting artist Paul Pfeiffer’s video and audio installation Three Figures in a Room.

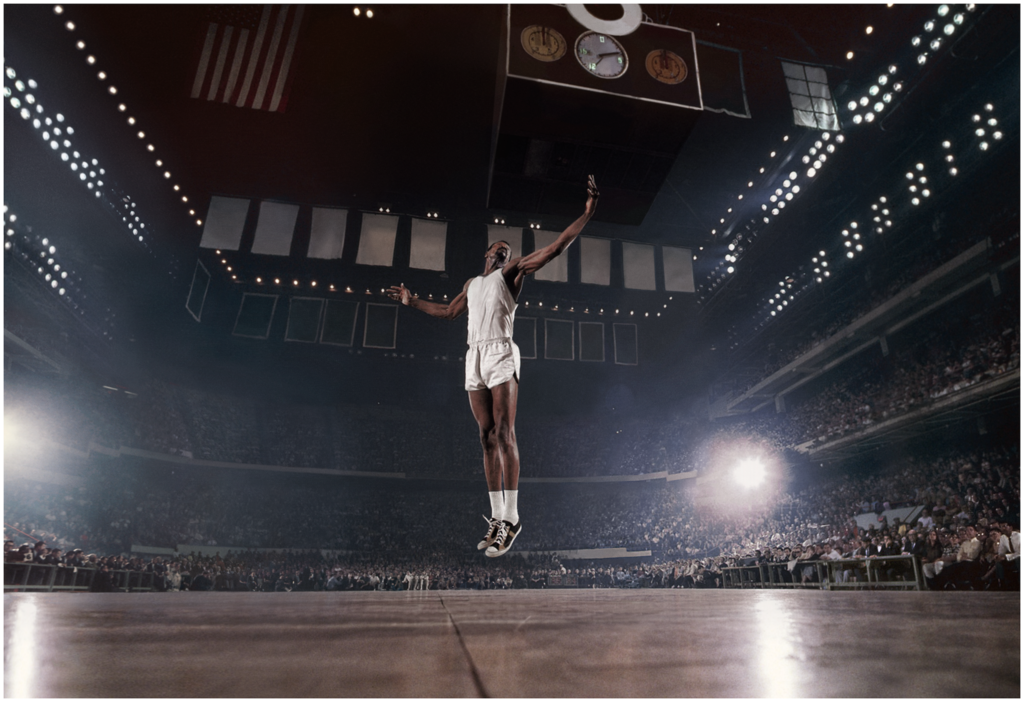

My eyes adjusted to the darkness. On the left screen, an elderly man, who spoke through subtitles, gleefully punched two red boxing gloves together. The man, who is a Foley artist, was reenacting the video on the right screen, where Manny Pacquiao landed a terrific blow to the head of Floyd Mayweather in what was dubbed, in 2015, “the Fight of the Century.”

The silent screen on the right that showed the fight was visually striking. Together, the screens’ audio and visual nature bled into each other. To accomplish this confluence, Pfeiffer hired the two accomplished Thai Foley artists seen on the left screen, Chad “Lek” Mahapitchayakul and Thanasak “Nhae” Julaked, to re-record the sounds of the Pacquiao-Mayweather fight.

The film of the men in their studio in Bangkok reveals the multi-layered relations inherent in the media production of delivering “reality” to a global audience. But I knew none of this yet.

Assembling my own meaning, I began making up a narrative: The old man was a former boxer reliving his glory days, I thought, and his family had settled him in front of the television, a screen as a pacifier. He was giving them a play-by-play of the fight. There was a microphone in front of him, and I tried to make out his language, his words, searching his surroundings for clues to where he was, what he was doing.

The process of being immersed in the unfolding action was curated by Pfeiffer: You are the third figure in the room. Each screen comprises separate realities. I had just superceded my surroundings, McCoy Pavilion, Ala Moana Beach Park, my family, giving all my attention to the old man, to Manny Pacquiao throwing the punch, to the opponent who just caught it in the side of the head, reeling.

It happened without me thinking, without me giving permission. It happened without me knowing that I had momentarily displaced my identities.

And all of this happened without me sensing the architect of this abstraction, the thief of my time and life: video artist, photographer, and sculptor Paul Pfeiffer. Hawai‘i born, raised in transit between Hawai‘i and homes in the Phillipines, and later in Navajo territory, where he finished high school, Pfeiffer might be called “Pinoy-Haole.”

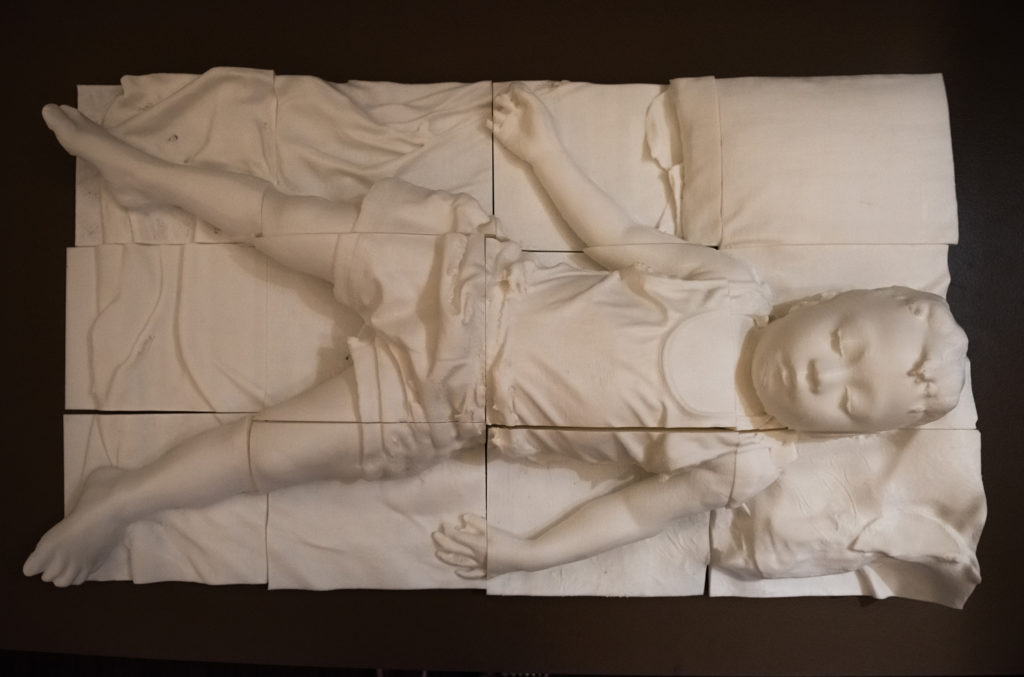

Pfeiffer’s work for the 2019 Honolulu Biennial, which also included the 3D print and sculptural installation “Poltergeist” at Bernice Pauahi Bishop Museum, engaged audiences in considering the way in which modern, capitalist society manipulates our senses, affective and intuitive, without using words.

Mediating between the visual layers in his piece, I watched as the Thai Foley artists scrutinized the fight in order to supply the correct sounds for the haptic elements of dance the boxers artfully employed. I watched the audience in the MGM Grand relish each blow. I saw Pacquiao and Mayweather eyeing one another warily, each landed punch making me recoil in expectation, as if it were my body at risk. I looked to my children to see if the violence of flesh smiting flesh was affecting them in ways I could not yet see. I asked if they wanted to leave the room.

While watching Pfeiffer’s piece, seeing and hearing became elevated states of concentration. The artist influences viewers’ states from screen to screen. He is a maestro that changed me like channels on a radio dial.

By supplying layers of participation, the artwork suggests that it is important to be attuned to the ways in which media manipulates our emotional states for its own purposes. Entertainment chips away at our tolerance for violence and consumption, numbing us to our own suffering, dulling or heightening our ability to empathize.

There are warnings to protect your eyes from being hurt by too much light on your cell phone, just as there are warnings about protecting your ears from music at a high volume. Yet there are no warnings to protect you from the way your emotions are played like an instrument, or attuned to resonate with invasive outside media stimulation.

The artwork suggests that it is important to be attuned to the ways in which media manipulates our emotional states for its own purposes

Noelani Arista

There are no warnings to protect you from the way split-second choices to engage in alternate realities twist or stunt our growth as individuals, as prospective lovers, as parents, as members of the community, routing our subjectivities away from lived relations in real time.

“I come from a printmaking background rather than a filmmaking background,” Pfeiffer commented when I described to him my experience of Three Figures in a Room.

In printmaking, he explained, you divide an image into layers of color or layers of pattern or texture in order to produce the whole.

“It’s a printmaker’s kind of subjectivity to think about how images or really reality exists in multiple channels or multiple layers.”

Pfeiffer noted that in Hollywood, everything in post-production is synced so that “the viewer’s consciouness is guided seamlessly through the story.” By offering audience members the opportunity to engage with different, dissembled layers of media reality, Pfeiffer has opened up a disturbance in our perception, allowing us to see our susceptibility to synthetic media realities.

His work reveals the effort it takes to displace one’s own relations and join the mediated reality of the TV screen, soundscape, and festival atmosphere of sports violence. Pfeiffer’s work shows that we have little agency as watchers, of onboarding portals of augmented, alternative, or virtual (un)reality via mobile applications, MP3s, music videos, gaming, television, and film.

Each moment of engagement alters our inner state—like wind ruffling the feathers on a bird, we are changed. Pfeiffer’s work gives us a glimpse of our future, if we can pay attention long enough to the realities we inhabit.