Text by Rae Sojot

Images by Michelle Mishina

Tom Sewell delights in documentation. Each morning, the artist hands over his iPhone to his assistant, Ines Gurovich, who downloads the photos he took the day before and selects highlights to print. She then assembles the prints into a montage and pastes it into an oversized journal. It’s an ambitious approach for a diary, but Sewell’s zeal for all things creative is insatiable.

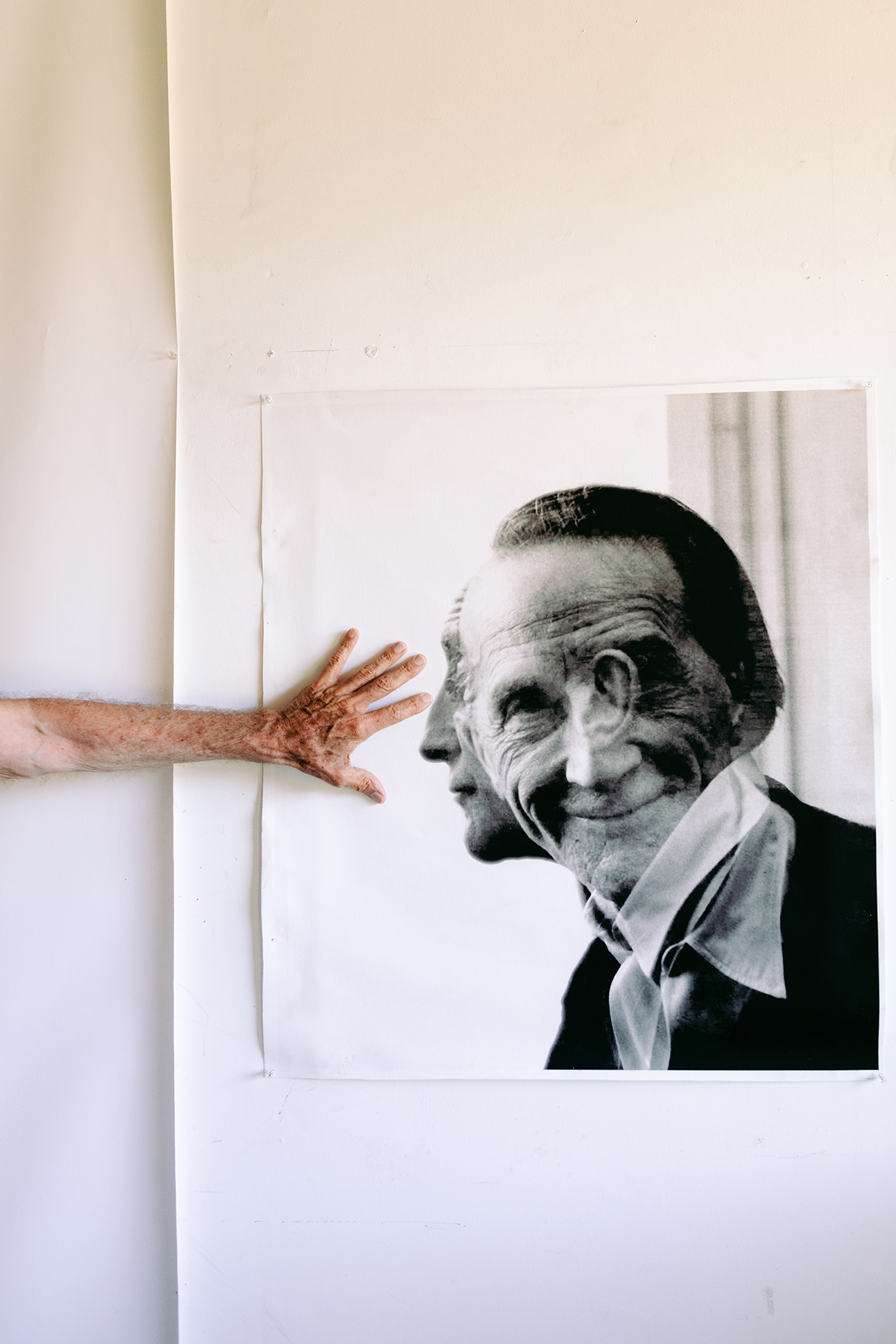

A multimedia artist and photographer based on Maui, Sewell believes one can find art anywhere and in any form. He certainly does. Now 80 years old, he has spent a lifetime collecting and creating, cultivating and celebrating experiences, places, sculptures, and friends. His specialty, however, is objet trouvé, or “found art.”

Growing up in Minnesota, Sewell was a tall, skinny kid, calm and a little self-conscious. His mother affectionately referred to him as “rug head” because of his mop of curls. By 19 years old, Sewell was trimming windows at Dayton’s Department store in Minneapolis. There, he met Joe Wright, an “educated, elegant, and stylish” gentleman who was the head of the display department. Wright left an indelible impression on Sewell, who began to emulate the dapper men of the downtown scene—the cut of their suits, the polished shoes, their knowledge of art and design.

“I’d wear a suit and tie and fedora hat and go to jazz clubs,” Sewell recalls. “I loved the idea of being grown up.”

Sewell’s immersion in art and culture laid the groundwork for a lifetime of creativity. He went on to run an art gallery in Minneapolis, work at the Minneapolis Institute of Art, and start a design magazine called Main. In the 1960s, Sewell moved to Southern California. In Venice, he began converting derelict industrial buildings into sought-after real estate. The endeavor proved lucrative, but for Sewell, it was the process of transforming nothing into something that enlivened him.

This leitmotif surfaced anew when Sewell settled on Maui in the ’90s. Here, he found inspiration in the most unlikely of scenes: the island’s declining sugar empire.

“The sugar mills were some of the ugliest, loudest places on Maui,” Sewell says.

Stepping into the industry’s rusting mechanical belly, Sewell marveled at the beauty in its brutality. Ideas surrounding duality of light and shadow, weight and lightness, decay and growth sprang to mind.

You May Also Like: Noah Harders’ Masked Mystique

For more than a decade, Sewell regularly visited the sugar mills and documented their activity.

“I was so interested in the colors and patina, design and decay, the juxtaposition of objects,” he says.

In 2006, he debuted “The Enigma of the Mill,” a grand art installation featuring giant giclée photo prints, panning video, and audio recordings. It was a mesmerizing panoply of sight, sound, and movement: thick streams of molasses pouring into vats; wet steaming pipes; close-ups of sprockets, cogs, and gears. The custom musical score, including pieces by Kronos Quartet and Xploding Plastix, was dominated by rhythmic clanging metal, its jarring notes woven alongside a stirring melody. To this day, even speaking about the installation stirs something wondrous within Sewell.

“The sugar mill is really my soul,” he says. His eyes glint as if a schoolboy with a gleeful secret. “Again, it’s that finding of art in the most unexpected places.”

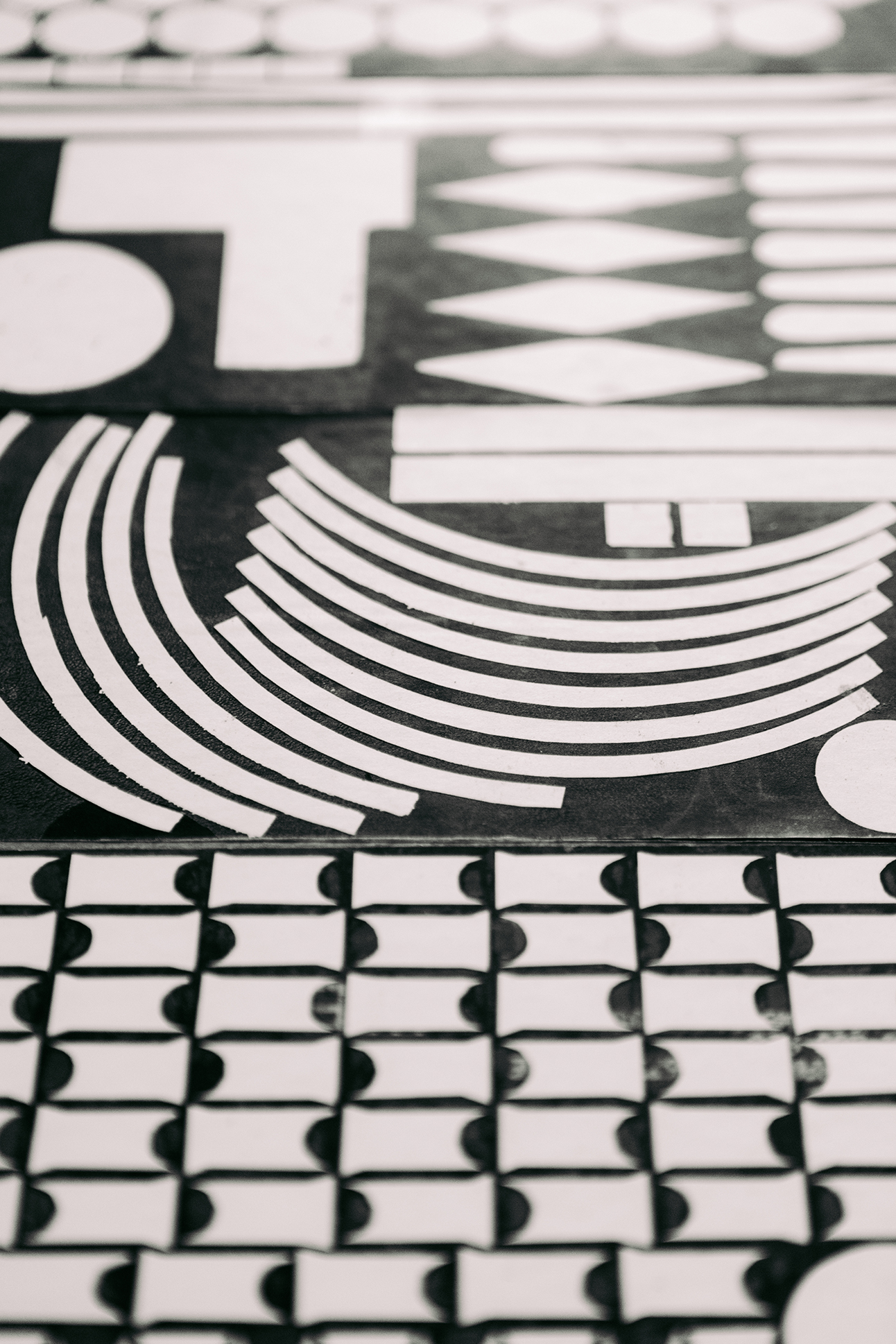

The art-making continues at the Ha‘ikū estate. Here, elements collected from the island’s sugar mills find a place in Sewell’s home and heart. Dotting the property are his large-scale sculptures, crafted from scrap bulk steel sheets salvaged from the Pā‘ia mill.

The sheets, arranged together vertically onto concrete slabs, are perforated with series of shapes: crescents and chevrons, triangles and trapezoids. Originally, the cut-outs were utilized as pieces for mill machinery, items such as blades, guides and seals. Today, their remaining negative spaces are whimsical plays on form and light. Sewell invites guests to sit, walk, and even dance within the sculptures.

“You should see what it’s like at night,” Sewell says. “It’s just beautiful.”