Text by Noelani Goodyear-Ka‘ōpua

Images by Ed Greevy and Franco Salmoiraghi, and courtesy of the Ritte ‘ohana

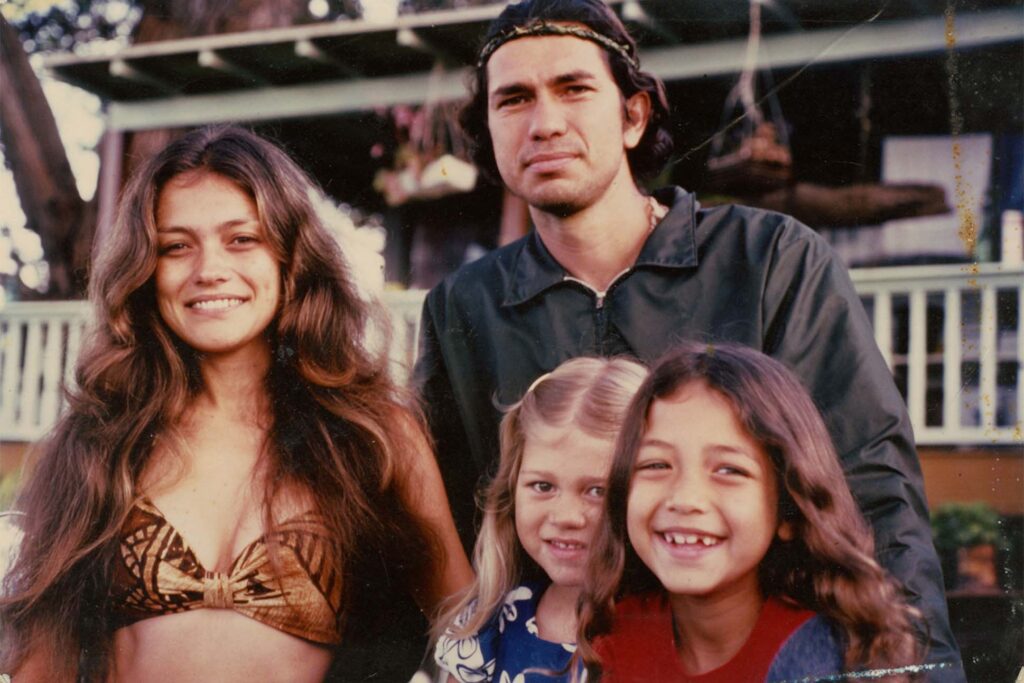

“On January 13, 1976, Loretta Ritte kissed her two daughters and signed temporary power of attorney to her mother-in-law. “It was a good day to die,” she says. Loretta and three others were heading out to protect the sacred Hawaiian island of Kaho‘olawe, which the U.S. Navy had been using as a live-fire target since World War II. They aimed to stop the military’s weapons testing and training by placing their bodies between the earth and the bombs the military planned to detonate on it. The group described their actions as aloha ‘āina, love of the land.

Loretta left her home on Moloka‘i by boat with her husband, Walter, her sister-in-law, Scarlett, and their friend Emmett Aluli. They slipped onto Kaho‘olawe at dusk and laid low until the morning. Then they hiked to the top of the island. “It was just shattered rocks and red, open wounds,” Loretta writes in Nā Wāhine Koa: Hawaiian Women for Sovereignty and Demilitarization, published in 2018.

It was all bare at the top. And yet it was really beautiful too. We were able to see Maui and Lāna‘i, and there was a calming effect, because we had nothing else. Everything else was stripped away. It was just you and her. You and her, and everything that came with her.

Loretta Ritte is one of many women who emerged as activists for aloha ‘āina in Hawai‘i in the 1970s. Yet far too often, their stories have gone untold and unrecognized. We sought to remedy this gap in popular memory with Nā Wāhine Koa, a book I edited featuring stories by Loretta Ritte, Moanike‘ala Akaka, Maxine Kahaulelio, and Terrilee Keko‘olani-Raymond.

Maxine Kahaulelio made the fifth landing on Kaho‘olawe with 13 others from O‘ahu in August 1977. At the time, Kahaulelio was a single mother of five working in a public-school cafeteria. She had also organized with local communities fighting eviction by large landowners and with women fighting for the dignity of their families while on welfare. “I will never forget the feeling of walking through the gun shells,” Kahaulelio writes in her chapter of Nā Wāhine Koa. “You could hear them: shack-shack, shack-shack. And every time I walk, my tears would fall, because every bullet was like, ‘Wow, can you imagine?’ We could have built beautiful schools. We could have restored beautiful fishponds and given our children food. Real food. Real education. Hospitals. We could break down the prisons and give restoration to our people, our brothers. Instead, millions and millions of dollars just to destroy the land. That’s what I saw on the ground. That’s what I was walking through.”

Nā Wāhine Koa features four Hawaiian women elders who participated in the early Kaho‘olawe movement and spent the better part of the next five decades working for the health and wellbeing of Hawai‘i’s lands and people. Maxine Kahaulelio, Loretta Ritte, Moanike‘ala Akaka, and Terrilee Keko‘olani-Raymond are wāhine koa, courageous women warriors. Each shares her story of coming into activism, of battles won and lost, of sustaining commitments to justice and aloha ‘āina. Between the four of them, they have protected freshwater supplies, Hawaiian burial sites, pristine rainforests, traditional fishing access trails, and more. They have resisted the use of toxic pesticides and weapons on Hawaiian lands, the construction of telescopes on sacred summits, and the eviction of mutiethnic communities by wealthy developers. They have asserted the importance of Hawaiian independence, demilitarization, and nuclear-free zones in Hawai‘i and the Pacific. Each has offered visions of peaceful and sustainable ways of living that honor the self-determination of Hawaiians and the humanity of diverse but oppressed peoples in the islands.

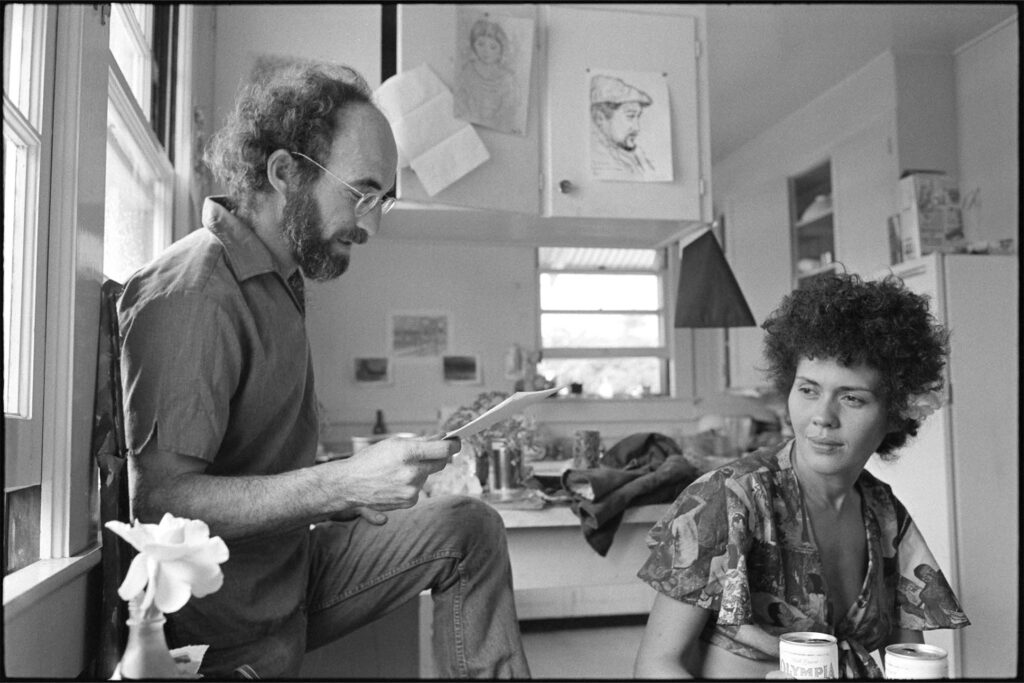

When we began the process of co-creating this book, these four fierce aunties welcomed me into their circles of memory. At their kitchen tables, on lānai, in restaurants and grocery stores, at coffee shops and bars, they poured out oceans of love for ‘āina, for extended families, for people who struggle. They shared stories over suitcases filled with water-damaged photos in Ziploc bags. They entrusted me with folders full of newspaper clippings and event flyers. They shared memories and analyses over food flavored with laughter, heartache, hope, and kuleana. When Haunani-Kay Trask wrote of “fine baskets of resilience to carry our daughters in,” she must have known this kind of love. These four wāhine koa are not the only women to have fought such battles or led Hawaiian movements for justice. Rather they exemplify the powerful and diverse roles that Hawaiian women have played in ongoing expressions of aloha ‘āina.

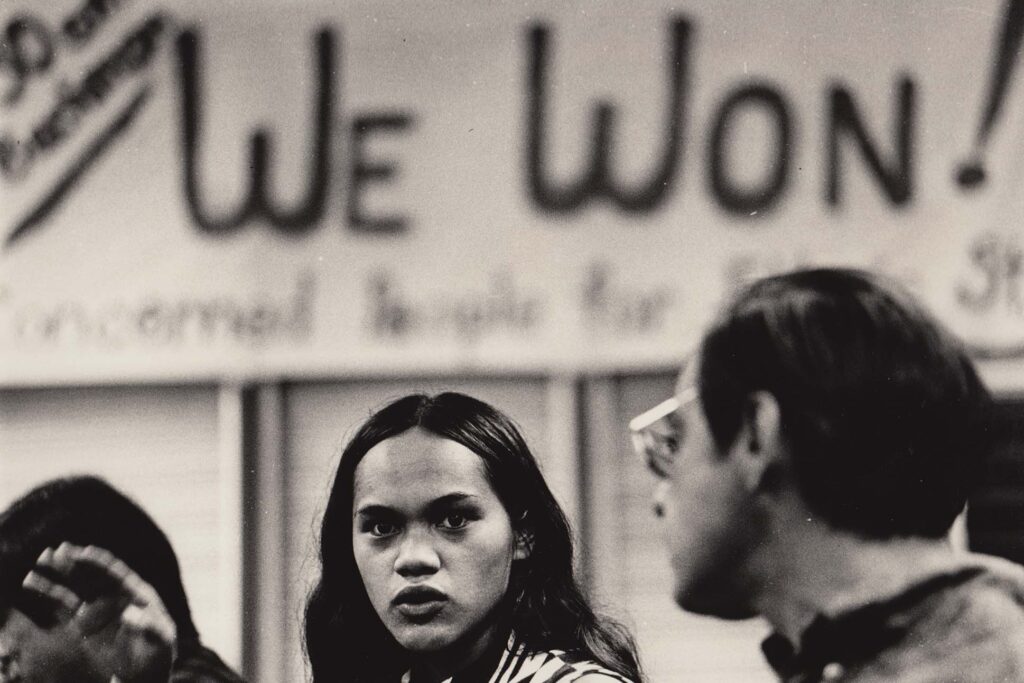

Right: Moanike‘ala Akaka, Honolulu, 1972.

When I asked Aunty Loretta why she continues to be active in her community on Moloka‘i, she talked about freedom, “the kine freedom when everyone takes care of each other, when everyone takes care of the ‘āina.” In the book, Loretta writes about experiencing an intensified version of this freedom when she and her family, along with four other couples, moved to the uninhabited northern valley of Pelekunu on Moloka‘i, where they lived off-grid for almost two years in the late 1970s.

One week, when she was alone with the kids in the valley, a huge storm engulfed them from sky and sea. Massive waves rolled into the beach. She and her children ran to the back of the valley. The heavens poured down heavy rains, thunder, and lightning. Roaring waterfalls lined the cliffs. And yet, Loretta felt empowered to protect her kids and survive the storm. “I don’t think I was ever afraid, because the valley was like a womb. A mama. A teacher. A protector,” she writes. “It was a good place, if you listened. It could be a bad place, if you nevah.”

Noelani Goodyear-Kaōpua is the author of Na Wāhine Koa: Hawaiian Women for Sovereignty and Demilitarization, published by University of Hawai’i Press. She’s an associate professor of political science at the University of Hawai’i at Mānoa.