Written by Sarah Burchard

Images by Philip Arneill, Mark Kushimi, and Katsumasa Kusunose

Though I love the crackling of vinyl records when paired with the taste of chilled whisky, that’s not why I’m drawn to the Japanese-style jazz joints cropping up around the country in recent years. No, it is the memory of my father at the piano, my mother queuing up LPs at home, and them singing duets while Dad jams a jazz riff, sipping two fingers of scotch. I have them to thank for my lifelong fascination with jazz.

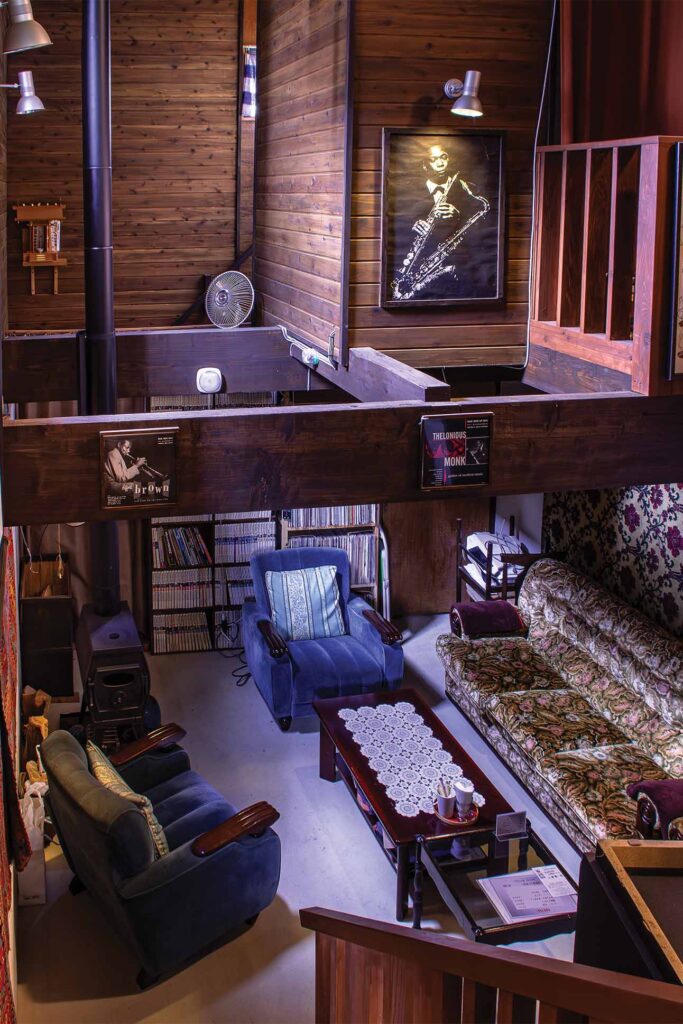

a listening bar inspired by JBS in Tokyo.

I only recently learned of Japan’s love affair with the genre, but it’s one that has been ongoing for a century. Jazz is thought to have been introduced to the country in the 1920s by way of luxury ocean liners traveling between the U.S. West Coast and Asia. Passengers and cruise-ship entertainers alike—including Japanese musicians returning from the U.S. and Filipino jazz bands who mastered the music under American occupation—would disembark in cities such as Osaka and Kobe, transforming establishments into gathering places for a burgeoning jazz community.

Japanese jazz lovers began bringing records back with them from America and opening kissaten, or coffee shops, devoted to the playing and appreciation of recorded jazz. During World War II, these jazu kissa, or jazz cafés, proliferated throughout Japan and became hubs of counterculture and pro-democracy ideas. Post-war, when foreign records were unaffordable for most fans to import, jazz venues soared in popularity. Local musicians came to study the form, seeking out hard-to-find editions among café owners’ robust record collections. Meanwhile, a surge in international travel brought a steady stream of touring American jazz musicians; today their visits are memorialized in signed record albums and photos displayed on the walls of jazz establishments throughout Japan. By the ’70s, Japan was home to more than 600 jazu kissa, including newer, more modern establishments that stayed open later, served alcohol, and featured high-end sound systems.

On a recent trip to Japan, I went searching for these kissa, starting with Bar Martha, a modern kissa in Tokyo. I found it in a dark alley among shuttered windows and rusty garage doors. A tiny light illuminated a lone sign hanging above the kissa’s entrance, barely big enough to read: “Bar.” Inside, a man in a Sublime T-shirt and a long, stick-straight ponytail pointed to a plaque explaining the house rules: no photos, no talking.

The bar was cavernous and bathed in amber light, with windowless walls of exposed brick and polished wood. In the far corner stood two rows of turntables with small desk lamps illuminating each deck. The surrounding shelves were lined with thousands of records. While this collection would be noteworthy elsewhere, regulars don’t bat an eye. Some kissa boast more than 10,000 records.

“Stormy Weather,” a ’30s torch song covered widely by jazz greats like Duke Ellington and Billie Holiday, played over the bar’s giant Tannoy speakers, which stood level with the spirits gleaming on the top shelf. Men in black suits sat quietly sipping highballs. Others wordlessly smoked cigars and drank whisky poured over giant spheres of ice. I imagine this kind of attentive listening was how my dad taught himself to play the piano growing up in New York, in the heyday of jazz and blues.

Visiting JBS Bar, one of the older kissa in Tokyo, was a different experience, although it, too, was tricky to find. On the third floor of a nondescript building on a quiet Shibuya street, a rolling door concealed an entryway bearing the letters “JBS.” The tiny, brightly lit space inside had three tables and a handful of seats at the bar. In contrast to dark and sultry Bar Martha, this had a welcome-to-my-living-room vibe, but the owner, an older gentleman with a bald head and black-rimmed glasses, had no desire to chat. Drink offerings were basic: beers and highballs. Like Bar Martha, photos are prohibited. Unlike Bar Martha, no free snacks.

(LEFT) Nefertiti, from the photobook series Jazz Kissa..

In the last decade, jazu kissa have spread beyond Japan. Music lovers, inspired by their experiences in the country, are opening their own versions back home. But even as these Japanese-style “listening bars” gain global popularity, jazu kissa are disappearing in their home country. About 100 have closed over the past 50 years. Owners retire or pass away; younger generations flock to cocktail bars and live music venues.

Still, they’re there if you know where to look, and nowhere does jazu kissa like Japan. At listening bars in America, the playlists are solid and the sound is crisp, but guests listen passively, more concerned with selfies and socializing. In Japan, a relentless attention to detail and strict rules help keep jazu kissa culture alive, if only for the die-hard few who continue to hold it in high regard.